When my 13-year-old granddaughter highly recommends an author, I listen. Last year she recommended Kimberly Brubaker Bradley's books, The War that Saved My Life and The War I Finally Won. I loved them both and immediately had to find out what else Bradley wrote. When I discovered Jefferson's Sons, it became a must-read. For those of you who have read my Half-Truths page, you'll see why.

Many years ago I read Sally Hemings: A Novel. The story of Jefferson's hidden romance with his slave has stayed with me. Bradley took the facts about that 38-year relationship and put "meat on the bones." The names of their seven children are historical facts. The author took those names, researched their backgrounds and the time period, and did an amazing job of imagining their stories. The story is so well-written that I had to keep reminding myself that it's a work of historical fiction.

As the Kirkus review points out, this book is told from the third-person point of view of two of the sons, Beverly and Madison, as well as from an enslaved boy. This last perspective provides important insights into the entire Jefferson story--contradictions and all. Bradley transitions so smoothly from one point of view into the next that I had to stop reading to realize what had just happened.

REVIEW

Sometimes I review books by typing out portions of the book (this is also a good way to learn how to write!). Since Bradley's re-creation is so powerful, I decided to do that this time.

The first perspective is from the oldest boy's POV, Beverly when he is about seven. His mother, Sally Hemmings, is the first speaker.

"There is nothing inside, either one of you, or anyone else--Joe Fossett or Uncle John or me or anyone--that makes you a slave, that says you have to be one, that says you're different from somebody who isn't a slave. This difference is other people--people who make laws and put other people into slavery and work to keep them there."

Mama's eyes blazed. "But you aren't really slaves either," she said. She rocked Maddy back and forth in her arms. "You remember that. You'll never be told and you'll never be beaten and when you turn twenty-one you'll be free...That's a promise. A promise your father made me about all the children we might have. You'll be free."

"How can he promise that?" Beverly asked. "He can't just make us free."

Mama paused, growing. "He can," she said.

"Because he's the president?

"Because he owns us," Mama said. "He owns all of Monticello. The buildings and the farms. The people too."

Harriet asked, "You mean, because he's our daddy?"

Mama shook her head. She said, "Because he's Master Jefferson." (p. 35)

****

About two years later, Mama gives Beverly a genealogy lesson. She draws lines to all of Beverly's great-grandparents so he can see he has seven white ancestors and one black ancestor.

Mama nodded. "The law says that any slave's children are always slaves, but it also says that any person who has seven out of eight white great-grandparents is legally white. So you and Harriet and Maddy are white people. You're slaves, but you're white."

"Nobody acts like I'm white," Beverly said.

"No. They won't, because you're a slave. But think on it, Beverly. Someday you won't be a slave. You'll be a free white man."

Beverly thought of the white people he knew. They got to be bosses, mostly, and they lived in nicer houses than the black people he knew. Still. "I don't want to be white," he said. "White people are mean."

"Not all of them," Mama said..."It's easier to be white," she said. "It's safer." (P. 82-83)

Two years later Mama sharply reproves him for talking about how Jefferson is his father in public. Family members and visitors often see the family resemblance between the two. She responds to his anger about the situation:

"It's already been in newspapers once, years ago, about me and your father, but he lived it down and it's mostly been forgotten. Somebody decides to publish the truth about you and your siblings, and guess what? You'd be famous. Thomas Jefferson's half-white son." Mama's eyes blazed. "A famous slave, Beverly. You'd never get away from it. You'd never really be free."

....

"If you pass for white you'll be safer and if you're known to be my son by Thomas Jefferson you will never be allowed to pass. (pp. 113-4).

In these conversations, Beverly learns powerful lessons about himself, his father, and the world.

****

About a third of the way into the narrative, the story shifts to Beverly's younger brother, James "Maddy" Hemming's. He longs to get his father's attention and when he hears that Master Jefferson's pet mockingbird died, he catches another one and brings it to him. The President pays him fifty cents which is a lot more money than Maddy had ever had before. But that's not what he was looking for.

The coins were cold in his hand. Inside the cage, the bird made a sudden, wild squawk, and beat its wings against the bars.

Maddy swallowed. The most awful feeling came over him, all at once, like water poured out of a bucket onto his head.

That bird had been free, and now it was a slave. From now on it has to live where Master Jefferson wanted it to live, eat what Master Jefferson gave it to eat, even whistle the songs Master Jefferson wanted it to sing. He, Maddy, had sold that bird into slavery. (p. 144)

****

Like his older brother Beverly, Maddy also struggles to understand the implications of his skin color. In an interchange with his friend, Maddy claims that he needs to learn to read for the time when he's going "to be white." After comparing the color of their hands his friend says. "I already know I'm not white." He paused again. "Neither are you."

***

When Master Jefferson sells his friend, Maddy is angry.

Harriet, his older sister, asks him, "What, "she said, "do you think slavery is?"

Maddy glared at her. Harried took no notice.

"I'll tell you," she said. "It's not having any say. Any choice. Not about you, not about your family, not about anything. Forget not having to work for someone. Forget not being paid. It's the way. The not having any say."

"I know that," Maddy said.

"You act like you don't. You act like you're just now discovering what everyone else understood all along." (p. 227)

"An interesting miniature portrait sold on eBay in 2012 which was said to be of Harriet Hemings. One of the papers inside the piece indicates the subject as "Harriett Hemings", president Thomas Jefferson had two daughter's with his slave Sally Hemings, named Harriett, one dying shortly after birth, and the other, often known as "Harriet II", was born at Monticello in 1801 and was known to be working in the textile factory by age 14. It was well known that she was very light skinned and could "pass for white". The interesting thing here that the artist truthfully portrayed was that although she had very light skin, she still had African American features."

As you can tell from these quotes, this is a powerful work of historical fiction. Although it is out of print--which I find hard to understand--it can still be bought through used books sites. Teachers, you'll find that is an important resource when your class is studying colonial America, black history, and slavery.

****

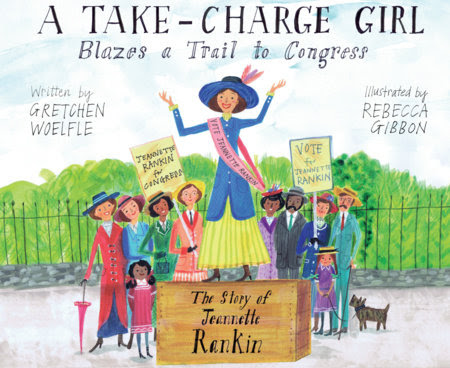

Congratulations to Julie Lyon for winning A TAKE CHARGE GIRL from last week's blog.

Don't forget to stop by Greg Pattridge's MMGM blog for more great MG books.